It’s not very often that neuroscience and PSHE are placed in the same sentence but it’s time to remedy that. The development of neuroscience, and the evidence of how the brain develops in adolescence, adds a strong case for the teaching of Personal Social Health Education (PSHE) in both primary and secondary schools.

There’s still an unhealthy scepticism about neuroscience. It’s in its infancy as far as scientific discovery – if compared with Newton’s Theory of Gravity or Einstein’s Theory of Relativity – but this doesn’t make it implausible or something that should be dismissed or ignored, and that is particularly so when we think of the type of education we are providing for our young people.

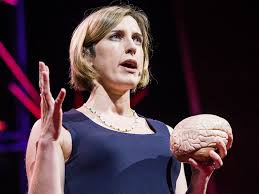

Sarah Jayne Blakemore, Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at University College London, did a talk at the Festival of Education entitled “The Teenage Brain”. A slightly truncated version can be seen here from a TEDGlobal event in 2012. For a longer version from the Royal Society, click here.

At Wellington College, Professor Blakemore made the following comments.

- Between the ages of 4 and 21 we lose grey matter to make room for used synapses (connections) to develop

- Excess synapses disappear or are pruned if they aren’t used – so environment is important

- Prefrontal Cortex- high level cognition, responsible for self-control, planning, inhibiting inappropriate actions, decision-making develops significantly in adolescence

- Therefore, risk-taking and impulsivity peaks during adolescence because the growth of the section of the Prefrontal Cortex, that understands and adapts to risk, isn’t developed.

- The limbic system, responsible for emotion and reward, in the brain is highly functional in adolescence, thereby more likely that behaviour is affected by peers

- The adolescent brain isn’t fixed. It’s malleable and strongly influenced by environment

- The ability to see other people’s perspective is developing in adolescence.

Essentially what this means is that the brain is still developing during adolescence and that this is probably a time when young people are most receptive to learning about social emotions – as their brains develop.

Therefore, isn’t this the time when we should be working with teenagers to make sense of themselves and others, where their synapses and connections are also developing – making room in the brain for youngsters to become socially and emotionally capable people?

Professor Blakemore used a quote from Shakespeare to show that the image of teenagers has long been relatively negative.

If we recognise, even from Elizabethan times, that this is a vulnerable time for young adults, then surely this is the absolute time when we should be addressing the issue of risk-taking and thereby potentially preventing behavioural factors that may contribute to teenage conception, use of drugs, erratic and irrational behaviour.

It’s also during adolescence that young people have a shift in their perspective of others. Professor Blakemore says she thinks that this can be directly attributed to how the brain functions and develops.

As young people progress through adolescence, then they gradually move from an egotistical to an empathetic perspective. Again, this is precisely what quality PSHE could support and develop.

An example was given of how inward looking teenagers have always been.

Letter to Guardian 2012

“There’s nothing like teenage diaries for putting momentous historical events in perspective. This is my entry for 20th July 1969…………I went to the Arts Centre (by myself!) in yellow cords and blouse. Ian was there but he didn’t speak to me. Got rhyme put in my handbag from someone who’s apparently got a crush on me. It’s Nicholas I think. UGH…………………..Man landed on moon.”

The sense of the social self develops significantly during adolescence which is why we, as adults and educators, should be doing our utmost to enable this development – early enough for it to make a difference. Neuroscience is now showing us that the optimum time to do this is in the post-13 year period of development when the prefrontal cortex is developing.

Professor Blakemore summarised her talk with four main points.

- The social brain develops structurally and functionally during adolescence

- Social cognitive behaviour changes during adolescence

- Peer acceptance is a major influence on adolescent typical behaviour

- Adolescence is an important time of opportunity for learning, creativity and development of self-identity

The implications for quality personal and social development, or PSHE, are significant. We need to talk to our young people about risky behaviour. We need to help them see the link and balance between what they intellectually perceive as sensible and what their instinctual selves might be telling them what to do.

We need to enable them to recognise emotions and the roles they play in their lives, and how they can manage these effectively for themselves and others with whom they interact. They need to talk about guilt and embarrassment – recognising, as Professor Blakemore says, the fact that these are social emotions that are reliant on “how someone else would think or feel about you” and compare these with raw emotions (basic or destructive) like fear and disgust that occur regardless or irrespective of consideration of others.

It’s not just about preventing risk. It’s about developing all aspects of the brain – and of life – adopting a multi-intelligent approach to life. The teenage brain isn’t dead. It’s alert, alive and ready to learn.

Professor Blakemore concluded her TED talk, and something similar at the Festival of Education, with this quote.

“This is a period of life when the brain is particularly adaptable and malleable. It’s a fantastic opportunity for learning and creativity. So what is sometimes seen as the problem with adolescence – hyper risk taking, poor impulse controls, self-consciousness shouldn’t be stigmatised. It actually reflects changes in the brain that provide excellent opportunity for education and social development”

We would agree, and yet, there is one slight contentious issue that we’d like to raise, noting that we are neither scientists nor neuroscientists – merely laymen.

This research doesn’t just have implications for how we teach teenagers now; it also has huge implications for Early Years and Primary education.

In her talk, Professor Blakemore discussed the different stages of brain development. A large amount of brain development starts at the back of the brain (with the visual development), moving forward to a concentrated development of the prefrontal cortex during adolescence. She reiterated what all good Early Years practitioners and parents also know – that the environment is vital for learning.

In order to develop our children’s brains, we need to give them every opportunity in Primary education, including a wealth of experiences – to be creative, to imagine, providing facts – in order that they can start developing the connections as they mature. Without a holistic approach to learning, there might be parts of the brain development that never happen. If certain aspects aren’t dealt with early in life, the opportunity for learning has gone. Grey matter, according to Professor Blakemore, disappears with the onset of adolescence. Synapses develop – the connections, but if the grey matter isn’t fully developed then the synapses can’t develop either.

Therefore, it’s not enough for primary education to be merely about the 3Rs. It has to be greater than that.

The other issue is this.

If we know that the prefrontal cortex, responsible for “self-control, planning, inhibiting inappropriate actions, problem solving, multi-tasking, decision-making, self-awareness and social interaction” continues to develop during adolescence, then could this development start earlier?

If we provide primary school children with proper opportunities for personal and social development, then could we avoid the risky activity associated with teenagers? If they have opportunities to develop this cognition and understand the significance of peer pressure before they are experiencing it, then could such behaviour be prevented, and could the positive understanding of human emotions and social interaction be accelerated, obviously being mindful of the younger child’s ability to understand?

If this were the case, then is there a possibility that in 10 or 20 years’ time, those that have experienced outstanding personal and social development education might, in FMRI scans, show that the prefrontal cortex is developing more rapidly?

It’s just a hypothesis, and one that we think links directly with our desire for a multi-intelligences approach to learning in all ages. If we develop the intellectual, instinctual, personal, social, spiritual and physical intelligences from birth equally, are our young people going to be more self-actualised, more evolved at an earlier age with all the positive implications for themselves, for their peers and indeed society?

It’s worth a thought!

……………………….

For more on neuroscience and mindfulness, click here for BBC Radio Four’s Start the Week programme, first broadcast Monday 30th June 2014

![brain [1]](https://3diassociates.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/brain-1.jpg?w=640)